If you can’t follow a license as easy as mine…

7 minute read

October 9, 2013, 3:21 PM

I am of the view that information deserves to be free, which is one of the reasons that I make my work available under a Creative Commons license. For those not familiar, I provide my content under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license. In a nutshell, that means that you are welcome to use materials found here for any purpose, including commercially, as long as you provide proper attribution, and share it under the same or similar license as you found it (it’s only fair, after all). I even wrote a guide on reuse of content found here. When I converted the site to WordPress, one of the changes that I made was to make the images available for download at full resolution. That was done specifically to help downstream users get what they need and get creating without assistance from me. That same conversion, with the image restoraton and such that went along with it, also finally allowed me to provide clean images right out of the box. Recall that at one point, I put my logo and URL in the corner of the large-size images for photo sets. Then I stopped doing that in 2005 or so, right around when I introduced the Creative Commons license to the site. The conversion and image restoration work removed all of the remaining tagged images, making every photo “clean” without any extraneous markings.

I like to think that I’m one of the more permissive and lenient content owners out there. Unlike many other entities that do not allow downstream use without explicit permission, I do allow downstream use right out of the box, as long as two things are present: attribution (preferably as “Ben Schumin/The Schumin Web”), and a free license. That’s not that hard to do, and by and large, most people who reuse content found here follow the license. But it really frosts my cookies when people don’t follow that, and because my license is so easy to meet, I take a very dim view toward noncompliance.

It always amazes me how many people think that because something is on the public Internet, that it’s public domain and can be used with wild abandon. It’s quite common. I’ve even had to disabuse my own mother of this notion before. Rather, just like any other medium, just because it exists does not mean that you have carte blanche to do whatever you want with it. Most material on the Internet is not, in fact, public domain, and therefore potential downstream users have to play by the content owner’s rules (or you don’t play). Those rules are up to the content owner.

Thus my love-hate relationship with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which is the law that created those copyright takedown notices that you may have heard about. You’ve probably seen screens similar to this before:

Image: YouTube (for a video where I had to do a takedown notice)

That’s what the end result of a DMCA takedown notice usually looks like. This is YouTube’s specific implementation of it, but most sites, especially those that contain user-generated content, have similar messages when they receive takedown notices.

I really despise when entities use DMCA takedown notices to silence their critics or stomp on instances of fair use. However, at the same time, DMCA takedown notices are the way that I enforce my Creative Commons license. My Creative Commons license says that yes, you can use it, but it’s not a blank check. If I see my work elsewhere on the Internet, my name had better be next to it, or close by it. And it’s amazing how many people choose not to follow such a simple request. Thus my view on noncompliance with my license is that if you can’t be bothered to follow my license, as permissive as it is, then I will file a DMCA notice for it and feel no remorse about it. Really. I will not lose any sleep over my sending a DMCA notice.

And honestly, I don’t like sending them. DMCA notices are a pain in the butt. They’re long, and they have very specific requirements for what needs to go into them, including my mailing address and phone number. They also have the potential to make people angry when they get them. But if the license isn’t met, then it needs to happen. The best thing that can happen after one of these things, though, is for the infringing party to get in touch with me afterwards. Realize that nine times out of ten, the lack of compliance is not intentional. There is usually no evidence of foul play, and thus it becomes a teachable moment. If I can instill a healthy respect for copyright and intellectual property in someone and share some best practices to keep them out of similar trouble in the future, then I’m satisfied.

Sometimes, however, my teachable moment backfires on me. I remember one incident on Facebook earlier this year where a person had borrowed a number of my photos of Afton Mountain from Schumin Web to use on their Facebook page about Afton Mountain. In this case, when I noticed the infringement, I initially reached out to the infringing party through a Facebook message. I explained what was wrong, and even offered to fix it myself and even add better versions of the same images (this was before the site had been converted to WordPress, thus the images at full resolution were not available online). The person behind the page identified themselves as a former coworker of mine from Walmart (small world!), and said that they would fix it. So I gave them the time and space to fix the issue. Several months went by, and the issue had not been corrected. Meanwhile, I engaged in normal discussion on the page and in a related group, as I found the subject matter interesting. But eventually it came to the point where my patience ran out with the noncompliance, and so I filed DMCA notices on all of the images in question. You want to talk about pissed off. The person in question was upset, but not so much about the fact that they were a copyright violator. Rather, they were mad that they got caught. Apparently, they thought that being a senior citizen meant that they could do whatever they wanted with wild abandon because in the “good old days” people did such things, and that they didn’t know that my images were “private” (whatever they meant by that). My explanations about my license and how to be in compliance fell on deaf ears. They ended up taking down all of the other images on that page that hadn’t been reported (I only reported my own, as those are the only ones that I have the legal right to issue takedown notices for), and then abandoned the page entirely, leaving this indignant message:

I started this community page March 2008 and have enjoyed it very very much.It has been such a pleasure seeing your old and new posts and sharing with everyone. Now I must delete it. The good news is I will start a new page in a couple weeks called “Our Afton Mountain”, where the Blue Ridge meets the Skyline Drive. I will transfer ALL photos to the new and improved “Our Afton Mountain” with more new photos. See you soon at “Our Afton Mountain”

That translates to, “I got caught breaking the rules, so rather than play by the rules, I’m taking my toys and leaving, and I’m going to post all of my infringing images somewhere else and hope I don’t get caught again.” The lesson about free content and license compliance was clearly not learned, and it’s because they absolutely refused to listen when told that they did something wrong and how to correct it. Instead, they blocked me. And good riddance to them. Favorite comment on the indignant post was, “[D]on’t let some punk bully you into changing your site[.]” Lesson definitely not learned by anyone, and apparently enforcing my own copyrights makes me a bully. Who would have thought? Though if they did end up launching their new page (I couldn’t find any evidence of such), it would definitely be foul play, since they were told – thus any infringement would then be willful.

Of course, don’t think that this is something that only happens on the Internet. This happens in the printed world as well. Remember that newspaper that I was holding up, and how I mentioned in the related Journal entry that there was an obscure Schumin Web reference? It was on the newspaper. Two of the images of Roanoke on the front page are my work (this one from Wikipedia, and this one from An Urban Comparison). The people who laid out that issue of The News Virginian used my images as free content, but failed to provide the attribution. I ended up talking with the editor-in-chief on the phone about that, and we worked it out. They apologized, and promised not to make that mistake again.

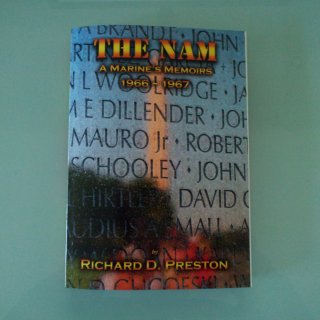

On the subject of mistakes that make their way into print, the best one is a recent instance where one of my photos made the cover of a book. Seriously, check it out:

This book is called The Nam: A Marine’s Memories, 1966-1967, by Richard D. Preston. You may recognize the photo on the cover as the lead from my Vietnam Memorial Photography set, as well as a photo feature in 2010. When I found out about this book, I was excited, and bought myself a copy of it on Amazon to have for my personal collection. I love seeing my work in print, after all, and like to get copies of such things if I can. Imagine my dismay, however, when I found out that there were no photo credits anywhere in the book. Thus the cover of this person’s book was a copyright violation. As this is a self-published book, my guess is that the author had no idea that they were supposed to do that. Of course, now I have to work with the author and the publishing company to see what can be done to rectify this situation, and also hopefully use this as a teachable moment for the author.

So the moral of the story is that just because it’s out there on the Internet doesn’t automatically mean that it’s public domain (though there are many great sources of legitimately public domain material online), and if you are at all doubtful, ask the content provider if it’s okay to reuse the material in question. Worst that someone can say is no. I for one appreciate when people start a dialogue and ask questions about license compliance, because it means that they’re interested in doing things correctly. Because after all, as I mentioned earlier, DMCA notices are a pain in the butt, but I’m not afraid to use them if necessary.

Postscript: On February 20, 2014, the Creative Commons license on The Schumin Web was discontinued, moving to an all-rights-reserved model.

Categories: Copyright infringement, Netculture, Schumin Web meta

Leave a Reply